ادامه 7.4 از مورد Framing bias تا وسط صفحه 228

In contrast suppose you are late for a job interview across town. You can speed, with a high chance of getting to the appointment on time, but also incurring the risk of getting caught by the police, fined, and be very late for the appointment. Alternatively you can choose to drive the speed limit, and certainly be slightly late. Here the choice is between two negatives, a risky one and a sure thing. You are “caught between a rock and a hard place”, and under such circumstances people tend to be risk-seeking. [413, 410]. The second of these contexts, the negative frame of choice, is often characteristic of real life decisions. For example, in addition to the speeding choice above, consider a company with major safety violations in its plant. Management can choose to invest heavy funding into addressing them through new equipment, hiring safety consultants, and pulling workers off the line for safety training, thus incurring the sure loss of time and money. Alternatively they can chose to take the risk that there will be neither a serious injury nor a surprise inspection from federal safety inspectors. All too-often, the framing bias will lead to an inclination toward the second option, at the expense of worker safety. A direct expression of this form of the framing bias is known as the sunk cost bias [414, 415]. This bias affects individual investors who hesitate to sell losing stocks (a certain loss), but tend to sell winning stocks to lock in a gain. Likewise, when you have invested a lot of money in a project that has “gone sour”, there is a tendency to keep it in the hopes that it will turn around. Similarly, managers and engineers tend to avoid admitting a certain cost when replacing obsolete equipment. The sunk cost bias describes the tendency to choose the risky loss over the sure one, even when the rational, expected value choice should be to abandon the project. Because people tend to incur greater risk in situations involving losses, decisions should be framed in terms of gains to counteract this tendency. Y Sunk cost bias makes it difficult for you to make money in the stock market. 7. Default heuristic. Faced with uncertainty regarding what choice to make people often adopt the default alternative [416]. Most countries use their drivers’ licenses to allow people to specify whether to donate their organs or not in the event of a fatal crash. Countries differ according to whether people need to opt in and decide to donate, or opt out and decide not to donate. Over 70% people follow the default and let the designers of the form decide for them. A similarly large effect is seen for people choosing to enroll in a retirement savings plan or having to opt out. Defaulting people into a retirement plan increased participation from about 50% to about 90% [417, 418].

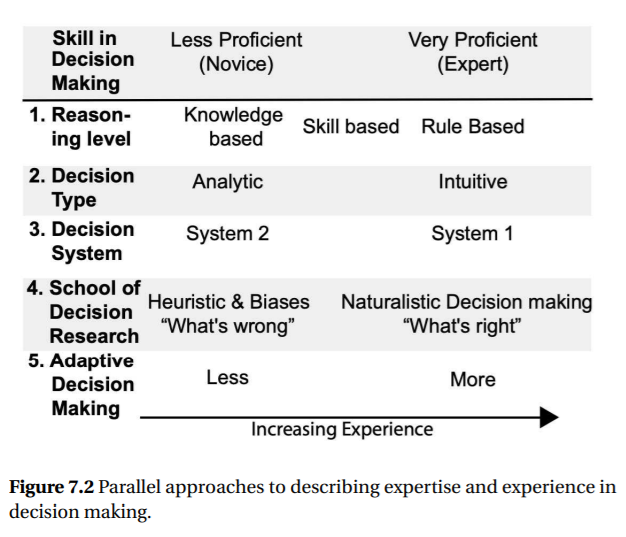

7.4.2 Benets of Heuristics and the Cost of Biases The long list of decision-making biases and heuristics above may suggest that people are not very effective decision makers in everyday situations, and might suggest that human contributions to decision making are a problem that should be fixed. However, this perspective neglect the fact that most people do make good decisions most of the time, and have the flexibility to deal with situations that can’t be reduced to an equation. The list of biases accounts for the infrequent circumstances, like the decision makers in the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, when decisions produce bad outcomes. One reason that most decisions are good, is that heuristics are accurate most of the time. A second reason is that people have a profile of resources: information-processing capabilities, experiences, and decision aids (e.g., a decision matrix) that they can adapt to the situations they face. Experts are proficient in adjusting their decision strategies. To the extent that people have sufficient resources and can adapt to them, they make good decisions. When people are not able to adapt, such as where people have little experience with the situations, poor decisions can result [357]. The focus can be either on the general high quality of most decisions, or on the errors due to biases associated with heuristics. Both of these approaches are equally valid, but focusing on the errors supports the search for human factors solutions to eliminate, or at least mitigate those biases that do show. It is to this that we now turn. 7.4.3 Principles for Improving Decision Making Decision making is often an iterative cycle in which decision makers are often adaptive, adjusting their response according to their experience, the task situation, cognitive ability, and the available decision-making aids. It is important to understand this adaptive decision process because system design, training, and decision aids need to support it. Attempts to improve decision making without understanding this process tend to fail. In this section, we briefly discuss some possibilities for improving human decision making: task redesign, including choice architecture and procedures; training; displays; and automated decision support systems. Task redesign. We often jump to the conclusion that poor performance in decision making means we must do something “to the person” to make him or her a better decision maker. However, sometimes a change in the system can support better decision making, eliminating the need for the person to change. As described in Chapter 1, decision making may be improved by task design. Changing the system should be considered before changing the person through training or even providing a computer-based decision aid. For example, consider the situation in which the removal of a few control rods led to a runaway nuclear reaction, which resulted in 3 deaths and 23 cases of exposure to high levels of radioactivity. Learning from this experience, reactor designers now create reactors that remain stable even when several control rods are removed [227]. Creating systems with greater stability leaves a greater margin for error in decisions and can also make it easier to develop accurate mental models. Choice architecture. The structure of the interaction influences choice in much the same way architecture of a building influences the movement of people through buildings [18]. Choice architects influence decisions by recognizing the natural cognitive tendencies we have discussed and presenting people with information and options that will take advantage of these tendencies to generate good decisions. The following principles show how choice architecture can nudge people towards decisions [419]. 1. Limit the number of options. Because too many options place a high burden on the decision maker, the number of options should be limited to the fewest number that will encourage exploration of options. Although the appropriate number depends on the specific elements of the decision maker and situation, four to five options where none is better on all dimensions. Fewer options should be offered if decision makers are less capable, such as older people, those in a time pressured situation, or less numerate decision makers faced with numerical options [420, 419]. 2. Select useful defaults. The effect of defaults on organ donation rates demonstrates the power of defaults: People often choose default options. Options for designing defaults include random, uniform choice for all users, forced choice, persistent default where the system remembers previous settings, and predictive default where the system picks based on user characteristics. If there is no time pressure and the choice is important then active choice should be used. If there is an obvious benefit to a particular choice then a uniform default for all users should be used, such when organizations select double-sided printing as the default [421]. As laptops, tablet and desktop computers, as well as phones, TVs and cars become more integrated predictive defaults become more feasible and valuable.

3. Make choices concrete. People focus on concrete immediate outcomes and tend to be overly optimistic about future regarding available time and money. To counteract people’s tendency to neglect the abstract future situation a limited window on opportunity can focus their attention like: “offer ends midnight tonight.” Another approach is to translate the abstract future value choices into immediate, salient consequence. For example, show people their future self so they can invest for that future self [422]. People who saw realistic computer renderings of older version of themselves invested more.

4. Create linear, comparable relationships. People tend to struggle to consider complex transformations and non-linear relationships. Transforming variables to their concrete linear equivalent promotes better decisions. For example, describing interest rates in terms of the number of payments to eliminate debt in three years is more effective than expecting people to calculate the non-linear, compounding effect of interest. Likewise, presenting fuel economy data in terms of gallons per 100 miles rather than miles per gallon, eliminates the mental transformation that is needed to compare vehicles [423]. The units presented should be those directly relevant to the decision.